It's

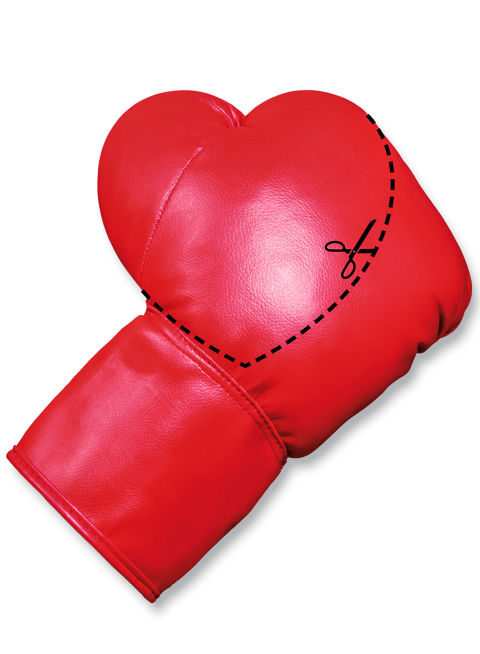

not necessarily a bad thing to fight. There are plenty of strong yet

volatile couples. But certain lines should not be crossed, and it's

important to repair. To do that, you need to validate the other person's

feelings and appreciate that he or she experiences things differently

than you do.

What most

people don't realize is that you're not actually fighting about money or

commitment or who does the housework. What you're really fighting about

is feeling a lack of love, respect, power … or some combination of the

three.

The Form Fights Take

The

content of your fight doesn't matter nearly as much as the form. If you

stood on a courtyard balcony and watched a bunch of other people

fighting on their balconies, you would see the same patterns play out over and over again.

The

first dynamic is when you gather evidence that reinforces your beliefs

and disregard evidence that challenges them. We call this confirmation

bias. You purposefully didn't call me yesterday because I don't matter to you.

Even if you told me, "I didn't realize not calling you would make you

feel that way, and I'm sorry," I'm still going to prove you wrong.

That's how crazy it is — I would rather have my confirmation bias proven

than to be relieved by hearing it's not true. That's because a

confirmation bias provides us with an order to our feelings, and we'd

often rather have a shitty order than no

order. You're convinced that only one person can be right — i.e., you —

rather than accepting that there's another person next to you who is

having a completely different experience of the same issue and has a

whole other point of view. That leads to a standoff.

The second dynamic at play in an argument is negative attribution theory. If I'm treating you poorly, it's because I had a bad day. If you're treating me poorly, it's because you're bad at relationships. It's the thinking that my experience is tied to a situation, but yours is based on your character and is about you as a person.

The

third is the negative escalation cycle. This is when we incite from a

person the very behavior we don't want. There's something in the

predictability of this that brings us a defeating certainty, even though

it's the opposite of what we long for. For instance, I'm going to talk

until you scream, then I'm going to say you're a screamer and I can

never get through to you. None of these dynamics are productive because

they lead to the same old fights. Moreover, we blame our partners for

escalating the arguments and fail to see how much we contribute to our

own misery.

The Big Mistakes Everyone Makes

Most

couples think that when they say something during a conflict, it is an

absolute truth rather than a reflection of an experience they felt in

that situation. If I feel it, then it must be a fact. If I feel you

don't care about me, then you don't care about me. Another thing that

makes fights go sour is using the words "always" and "never." I always do all the cleaning/You never help with the cleaning. It leaves the other person with no option but to refute what you just said about him, to stonewall you, or to attack you for your

offenses. What else is he supposed to do? You've just said that it's a

fact that he is a terrible person. Nobody likes to be defined by someone

else.

Another mistake

is chronic criticism — when you criticize so much that you leave the

other person feeling like he can never do anything right. (That's how

contempt builds, and contempt is the kiss of death in a relationship.)

The truth is, a criticism is often a veiled wish. When I say, "You never

do the dishes," what I really mean to say is, "I'd love for you to do

them more." But I don't say that because it makes me vulnerable. If I

put myself out there and say, "I would really like this," and then you

don't do it, I have to think that you don't care.

The Bad Patterns to Break

A

classic form of help comes from switching from reacting to reflecting.

When you're having a conflict, before you disagree with your partner,

try telling her what you heard her say. Research shows that when you're

in a disagreement, you're generally capable of repeating what the other

person said for only 10 seconds. After that, you go into your rebuttal

or tune out. But it's important to repeat what was said so she feels

acknowledged. What I'm hearing you say is that when I do this at these moments, you feel X.

It's

also helpful to use a method developed by relationship scholar John

Gottman and colleagues called an XYZ statement: When you do X in

situation Y, I feel Z. When we're out with friends and you cut me off, I feel put down.

I'm not telling you that's what you're doing, I'm telling you how I'm

feeling. (You can argue with how a person defines you but not with how a

person feels.) This also helps defuse escalating fights because it

forces you to slow down and think about what you're trying to say, and

then the other person has to repeat it.

Ad

Next

comes validating and empathizing. People fight because they want to

feel that they matter, that the other person respects what they're going

through. A simple "I can see where you're coming from" is deeply

validating. When your experience is acknowledged, you feel sane.

No comments:

Post a Comment